Originally posted at Patell and Waterman’s History of New York.

Next up in our series of Q&As with Networked New York participants is Joey McGarvey, who recently graduated from NYU with her M.A. who recently graduated from NYU with her M.A. degree. McGarvey is also an editorial assistant at Knopf. Her paper at the conference, “‘The Good, the Great, and the Gifted’: An Introduction to the New York Fruit Festival,” was taken from her master’s thesis, which won the 2012 Rose and Herbert H. Hirschhorn Thesis Award.

Though previous critics have touched on the Fruit Festival, your paper insists on a fuller and more complete understanding of its cultural importance. How would you briefly describe the significance of the Fruit Festival to the 19th-century literary and cultural history of New York City?

The Fruit Festival wasn’t entirely anomalous. A similar event for literary tradesmen—not involving fruit—was held in the 1830s, and in the decades after the Festival large birthday celebrations were thrown for various authors. But the Festival occurred at a particularly dynamic moment in American literary history. Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World (1850) and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) had both been huge bestsellers in the years immediately preceding the Festival, and of course there are all of the canonical masterpieces by male authors, including Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850), Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851) and Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854). There was a lot at stake in literary culture of the period—establishing copyright laws, for example—but managing authorship and the relations of authors, publishers, and readers was, it seems to me, most crucially at the heart of the Festival.

Also especially important for New York City, and another underlying reason for the Festival, was the competition among the big publishing cities—New York, Boston, and Philadelphia—to be the literary capital of America. New York was more or less there by 1855, when the Festival was held, but Boston was still very much alive and vibrant. At the Festival, the Boston-based publisher Uriel Crocker introduced the speech of his colleague, James T. Fields, by saying, “Though we stand on the soil of New York, there is at hand a fine Boston Field, from which we have often reaped great harvests, and as this is a fruit festival, and the fruit gathered from this Field is always pleasant to the taste.” Putnam, in turn, noted in his Festival speech, “The issues of our presses in about eighteen months would make a belt, two feet wide, printed on both sides, which would stretch from New York to the Moon!” New York, mind you—not earth, not America, and certainly not Boston or Philadelphia.

Why fruit and why a Fruit Festival?

Pragmatic reasons: much of the press coverage notes that absence of liquor, wine, and cigars, all hallmarks of male gatherings, and in their letters, several of the women express anxiety about the dangers of the Festival’s mixed company (female guests were outnumbered 14:1). But also for bigger reasons, related to the Festival’s place in nineteenth-century American literary culture. The publishers organized the event to celebrate the boom in American literature in mid-century, and fruit obviously stands in for that growing body of native-produced books—as professor and encyclopedist Francis Lieber writes in his letter, “The varied fruits on your wide-spread tables . . . will be fit representatives of our literature.”

But fruit, I argue, also represents women, especially women writers, and is deployed by Putnam and the other publishers to metaphorically circumscribe female authorship. Just as Putnam had the countryside’s finest fruit imported to the city for the Festival—and he did, so much so that twenty-one varieties of pear alone were served—so did he pluck and transport these women writers from the smaller villages, towns, and cities of New England to New York. In the second chapter of my thesis, which I’m just about to finish, I discuss the counter-metaphor of authorship developed by these women in their periodical tales of the 1830s through 1850s, based on the twinned concepts of mobility and home (and working out the dangers and opportunities of each).

How did the Festival provide a space and an opportunity for professional networks of writers and other agents of culture to emerge and become visible, accessible?

In lots of ways. What’s a more visible representation of a professional network—especially as it intersects in one hyper-connected node—than Putnam’s scrapbook? Also, as a number of those scholars mentioned above have noted (for example, Michael Newbury, in Figuring Authorship in Antebellum America), the Festival was one of the first real celebrations of celebrity in America. Authors, especially women authors, weren’t always comfortable with what celebrity meant; like fruit, again, being a literary celebrity meant that you could be commodified and consumed by your audience. But collecting all of these prominent figures in one place meant getting to put faces to names—a literary pantheon made very visible, and almost within reach, of the fans who filled the galleries of the Crystal Palace, where the Festival was held.

What archival materials were most central to your project? What was your most surprising or unexpected find and how did that shape the story you tell with your project?

I spent a lot of time with the New York Book Publishers Association Records at the New York Public Library—the archive that underpinned my entire project. Basically, and I’m passing along what I’ve been told by the (awesome) librarians there, the NYPL has this small but really terrific collection of papers related to the New York-based publisher George Palmer Putnam. In the 1940s, they acquired a two-volume scrapbook that seems to have been assembled by Putnam himself (he was a huge scrapbooker, and a noted autograph collector as well), containing 190 RSVP letters from notables invited to the Festival. It seems like the scrapbooks were originally intended to be part of the Putnam papers, but eventually became their own archive.

Two of the potentially most important letters for my project are actually missing from the archive—a handwritten table of contents at the beginning of the first volume mentions letters from the writers Sara Payson Willis (Fanny Fern) and Susan Warner, but they’re no longer in the scrapbooks. That being said, there are wonderful letters—letters that help us to approach the Festival from a textual as well as historical angle—from women writers including Sarah Josepha Hale, Sara Clarke Lippincott (Grace Greenwood), Susan Fenimore Cooper, and Catharine Esther Beecher. And while this isn’t very professional of me, I’ll admit that I nearly wept when I saw Melville’s letter to Putnam, which actually constitutes its own puzzle.

Photo and quotes from letters courtesy of the New York Public Library: New York Book Publishers Association records. Manuscripts and Archives Division. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Joey says: This letter from Sarah Josepha Hale appears in one of Putnam’s scrapbooks. This photo gives viewers a good sense of the material nature of the archive—you can see the brightly colored paper that comprises the scrapbook, and you can also see that Hale’s letter is firmly attached to the page on the right—but also hints at the relation between New York and the other towns and cities these women writers called home. Hale, from Philadelphia, writes on this page, “I do not like to incur the risk of such fatal accidents as have, of late, happened on the mid-route between the two cities. I should go without fear of danger if duty made it necessary, but in ‘the pursuit of happiness’ I think we should take personal safety into the account.”

Though you were unable to attend in person, you were an active participant in the tweeting of the conference. What immediate questions or concerns did you take away from the conference?

It was pretty surreal to watch responses to my paper—which was read by Annie Abrams, one of the conference organizers—live-tweeted. Presenting a paper to an audience is anxiety-provoking, but your performance can also shield the paper (i.e., maybe if I move through this point quickly, no one will notice the gap in my argument). When someone else reads your paper, and you’re not even there to hear it, you feel naked, like your thoughts and their weaknesses are utterly exposed and vulnerable. That being said, Annie apparently did a terrific job. People laughed, which was definitely one of my goals—if you wrote a paper about the Fruit Festival and it wasn’t somewhat funny, you’d be missing something.

Certainly one question I left the conference with is what constitutes a city—how a city isn’t just constructed from buildings, bridges, or borders, but emerges from networks. Perhaps the city, like Putnam within literary culture, is just a node; that seems obvious when you look at a map but is somewhat less obvious when you live in New York. If you’re a resident here, you feel mutually embedded with millions of other people in this mass of concrete, not necessarily like you’re being connected by it. But that’s what the Festival was meant to do, to make New York the center of a network of authors, booksellers, and publishers. Even the Crystal Palace, which stood where the NYPL and Bryant Park now are, hovered near the midpoint of Manhattan (if not New York as it existed in 1855).

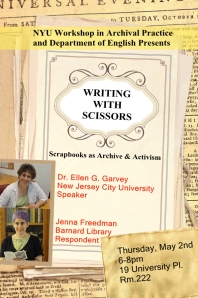

It is with great excitement that we invite you to our upcoming workshop with Ellen Gruber Garvey, Professor of English and Women’s and Gender Studies at New Jersey City University and the author of a new book, Writing With Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford UP, 2012). Please join us on May 2, 6:00-8:00 PM at 19 University Place, Room 222. The event is free and open to the public and refreshments will be served.

It is with great excitement that we invite you to our upcoming workshop with Ellen Gruber Garvey, Professor of English and Women’s and Gender Studies at New Jersey City University and the author of a new book, Writing With Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford UP, 2012). Please join us on May 2, 6:00-8:00 PM at 19 University Place, Room 222. The event is free and open to the public and refreshments will be served.